|

KROTOV'S DAILY

February 16, 2002, Moscow, 8.57

Tue Feb 12, 2:06 PM ET

By SARAH KARUSH, Associated Press Writer

VLADIMIR,

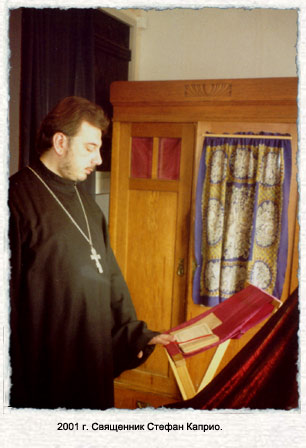

Russia - On a wintry Sunday in a small Catholic church, the Rev. Stefano Caprio's

deep voice resonates from the altar, carrying Russian words flavored with a melodic

Italian accent toward the congregation. VLADIMIR,

Russia - On a wintry Sunday in a small Catholic church, the Rev. Stefano Caprio's

deep voice resonates from the altar, carrying Russian words flavored with a melodic

Italian accent toward the congregation.

The distinctive sound of Caprio celebrating Mass in the city of

Vladimir is symbolic of Roman Catholicism in Russia, where some

200 foreign priests are helping to revive a community nearly snuffed

out by 74 years of communism.

Their presence has riled the dominant Russian Orthodox Church,

which contends Catholic priests are importing an alien faith and

attempting to lead people away from Russia's native church, itself

recovering from decades of Soviet repression.

The Catholic Church's activities in Russia took on a new permanence

Monday, when the Vatican elevated its apostolic administrations

there to full-fledged dioceses. The more informal structure gave

the church the flexibility it needed to operate during the communist

era, but now, the church says, dioceses can better perform pastoral

duties. The new structure also allows closer Vatican control.

The Russian Orthodox Church reacted angrily to the announcement,

and the Orthodox Church's chief of foreign relations, Metropolitan

Kirill, told Russia's RTR state television his church would likely

stop all contacts with the Vatican indefinitely.

Tension intensified last summer when Pope John Paul II visited

Ukraine. The pope has long expressed a desire to come to Russia,

but the head of the Russian Orthodox Church, Patriarch Alexy II,

says he will oppose a papal visit as long as the Catholic Church

continues its alleged proselytizing on Russian soil.

In Vladimir, about 100 miles east of Moscow, the spire of the 108-year-old

Our Lady of the Holy Rosary shares the skyline with the golden onion

domes of ancient Orthodox churches.

To Catholic parishioners, there is nothing foreign about their

church. And Caprio, who came to Vladimir in 1994, has become a vital

part of the community.

"This church answered my needs," said 42-year-old Irina Ignatyeva,

adding she was drawn to Catholicism because of her Polish great-grandmother.

Before the 1917 Revolution, Catholic worshippers here were primarily

foreign traders. Today, the majority of the 500 parishioners are,

Caprio said, "ethnic Catholics" � Russians with Polish, Belarusian,

Lithuanian or German roots.

During the Soviet era, Our Lady of the Holy Rosary was converted

into apartments and then into a museum, and its bell tower became

a radio relay center.

On a recent Sunday, about 100 people packed the church for Mass.

Afterward, younger parishioners performed humorous skits as a birthday

surprise for Caprio, who turned 42 the next day.

Prior to 1917, Catholics in Russia numbered about 800,000. In 1991,

when the church began restoring its structure under the leadership

of Archbishop Tadeusz Kondrusiewicz, there were only 10 parishes

and eight priests.

Kondrusiewicz now puts the number of Catholics in the country at

about 600,000. There are 212 parishes and nearly 300 small, unregistered

communities. In 1999, the first priests were ordained in post-Soviet

Russia, and today about 15 percent of the country's 275 Catholic

priests are Russian, Kondrusiewicz says.

The Catholic Church says it is merely restoring what existed before

the revolution and cannot be accused of invading Orthodox territory.

"They are lying when they talk about proselytizing.... I have never

heard a concrete example," Caprio said, anger rising in his voice.

"The Orthodox Church's main mistake is that it has always defined

itself in opposition to an enemy."

Despite the arguments between the Catholic and Orthodox hierarchies,

church relations in Vladimir are friendly. Caprio and the local

Orthodox bishop visit prisons together, and the churches are building

an interfaith youth center.

This contrasts with other regions, where local officials' have

favored Orthodox churches and prevented Catholic parishes from reclaiming

church property.

The Rev. Maxim Kozlov, an Orthodox priest who teaches comparative

theology in Moscow, says the number of so-called ethnic Catholics

in Russia does not justify the extent of Catholic Church activity.

He says the church is looking toward Russia to renew its flock and

recruit priests.

"They build churches in (the Siberian cities of) Irkutsk and Novosibirsk

on the basis of 'there once was a church here,'" Kozlov said. "But

the Poles and Germans are long gone from those places."

Some worshippers say they felt drawn to Catholicism, which differs

from Orthodoxy not only in theology, but also in more tangible ways.

During the Orthodox liturgy, congregants stand in an often dark

church filled with the smell of candle wax. Women must wear skirts

and cover their heads. The liturgy is said in Church Slavonic, a

relative of Russian not immediately understandable to Russians without

religious education.

At Holy Rosary, light streams in the windows and congregants sit

for most of the Mass. Many women wear pants, and the language is

Russian.

"Here there is real faith without abridgment of freedoms," said

Yulia Popkova, Holy Rosary's 24-year-old choir director, who said

she joined the church after becoming disillusioned with her Orthodox

parish.

|